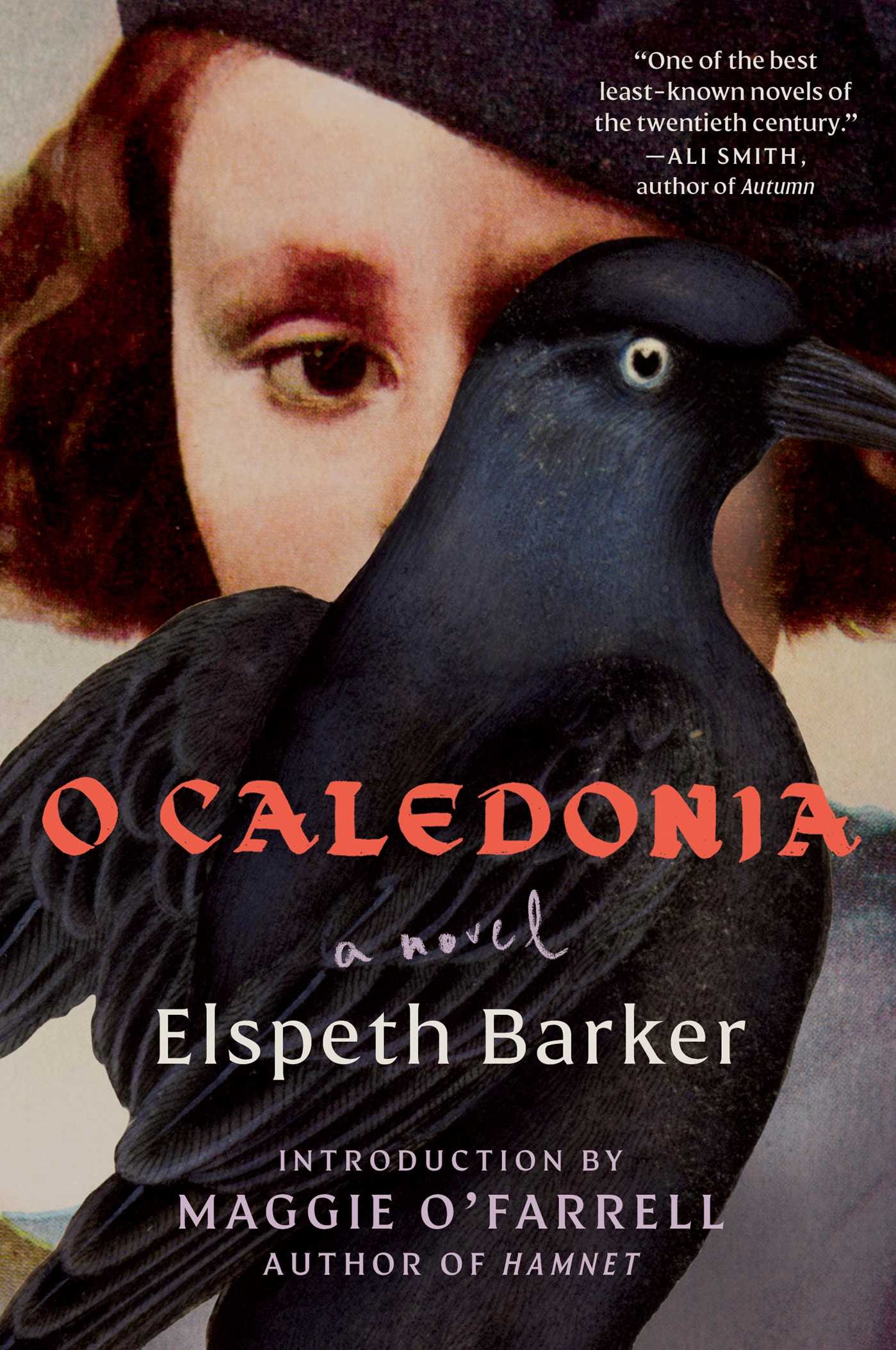

Why I ❤️ "O Caledonia" by Elspeth Barker

The Books We ❤️ Club welcomes ... Mr. Troy Ford

Lucky for everyone, I’ll dispense with the usual formality of introducing my guest writer and book and adding some pithy, ridiculous or obscure association I have to the book in question because this month’s edition is by me, and I’ll get to all of that in a jiff.

Happy reading! ~ MTF

The Books We ❤️ Club—the book club you don’t actually have to read the book, leave the house, or even change out of your jammies to enjoy—as writers sing the praises of books that reach into our hearts.

We invite you to add your own reactions, insights, and ideas in the Comments for an impromptu book club session. Share your favorite quotes, characters, moments, and surprises in discussion with other passionate readers.

(And if you’d like to feature your favorite book in a future edition, DM me.)

NEXT TIME: “Why I ❤️ Cold Comfort Farm by Stella Gibbons” with of and

Why I ❤️ O Caledonia by Elspeth Barker

I once decided to become friends with someone on the sole basis that she named O Caledonia as her favorite book; I’m happy to report that it was a decision I’ve never had cause to regret. — Maggie O’Farrell

How did I go 31 years never hearing the name of Elspeth Barker or the title O Caledonia? Such are the vagaries of books and publishing and squeaky wheels.

Such, too perhaps, a consequence of this being the only book Barker ever published, and a little later in her game than the usual wisdom advises. She was 51, and as another over-50 debut author, I can attest that the hunger and bravado of youth account for much of the trumpeting that age finds less and less appealing.

Still, she lived to the respectable age of 82, and her death in 2022 precipitated a reawakened appreciation of her slim but mighty legacy—also the article by fellow Scottish novelist Maggie O’Farrell in Lithub (a reprint of the introduction from the posthumous edition) which introduced me to “One of the best least-known novels of the twentieth century.”

I’ve said she’s a literary one-hit wonder, but I would emphasize wonder in a way it’s rarely meant: I’ve read this book three times since 2022, and it is in the Top 3 of my Desert Island Books List.

She only needed to write one book, O Caledonia is that good.

I will offer no spoilers because much of the magic lies in the unexpected stings of brittle hilarity which befall the heroine of the story, young Janet of Auchnasaugh, the cold, damp manor which sets the stage for this Gothic tale of 1950s feminine censure.

The house itself is a character in its own right.

Indeed, for her Auchnasaugh was a place of delight and absolute beauty, all her soul had ever yearned for, so although she could understand that many a spirit might wish to return to it, and hoped that in time she too might do so, she felt the circumstances and mood of such visitations could only be joyous.

And while the lush descriptions of house and Scottish Highlands permeate every chapter and scene with foreboding, it really is the black humor woven throughout which sweetens the delicious horror.

I hesitate to give specific examples, but here I hint anyway—from dentures to puffball mushrooms to the sternest Nanny ever, each moment of perfect folly a treasure. If it were possible to quote the entire book, I would, but I’m already flirting with copyright infringement, and it would make this review quite redundant.

Instead I can simply offer a few excerpts which capture the trials of the brave and contrary Janet, who might find slight solace today in the pantheon of neurodivergent archetypes.

Like a great-granddaughter of Victorian madwomen in the attic, Janet (no last name) is a girl living out of time with society and her family, and receives her ultimate verdict for simply existing with more cleverness, passion, and caring than the people who should love her most.

She discovers the hard truth of her life early on.

Janet had heard Vera telling her friend Constance that she only really liked babies and found children annoying. In fact, she had said, it was possible for a mother to dislike her own child. Constance, who was childless and a psychologist, had much enjoyed this confidence and embarked on a lengthy interpretation … Her suspicions about Vera were now confirmed. Anyhow she had no need for a mother.

And although she faces it soberly, this cold faithlessness of her mother and family turns to a heartbreaking internalization.

She knew she was behaving horribly, she knew that she was indeed horrible, a despicable compound of arrogance, covetousness, and self-centred rage. She was like one of those seething, stinking mud spouts which boil up in Iceland and lob burning rocks at passers-by. She felt guilt for blighting Vera’s pleasure and excitement; she felt shame. Her shame and guilt only made her angrier. Where would it end? Her heart was pounding; any moment she might burst.

The precipitating event? Yet another episode of absurdity when Janet discovers her mother in the dining room painting a Shetland pony’s hooves gold, and rightly protests that it could be toxic to the animal.

Midway through, she comes across pictures in a magazine of the victims of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and is shaken to her core.

Her heart was hardened … She could no longer have faith in God or man. She transferred any religious impulse which might yet linger within her to the Greek gods, who did not even pretend to care especially for humanity or to value its efforts and aspirations, being far too busy with their own competing plots, feuds, and passions. Now when she prayed she stood in darkness, beneath the moon, and repeated her message three times, with rigidly clenched fists and unwinking stare, forcing all her strength upwards to the chilly disc or crescent which sometimes glanced slyly back at her.

Like the youngest member of the Weird Sisters, her growing dismay with the callousness of the world is tempered by sly flashes of grim humor:

What fun she would have as a ghost. She could hardly wait.

Time and again, Janet proves herself deeply humane, a fierce lover of nature and protector of animals—a maimed pigeon, her pet jackdaw, and Rosie, her own pony whom she alone cares for; time and again, she is dismissed for her pity, her intelligence, and her refusal to be tamed to the last.

To say I found in Janet and Barker kindred spirits would be playing it cooler than I am.

This is a coming-of-age tale first, and the meanderings of Janet’s life from birth to age 16 provide all the drama and tension one requires. The story itself does not follow a plot per se except to provide at the end the denouement revealed at the beginning.

Much of the pleasure of reading is in Barker’s language, how with each perfectly selected verb and adjective she infuses Janet’s world with an intelligence all its own. She is wildly articulate, nearly every sentence turned to perfection.

As I do, I peeked at some of the one-star reviews on the Goodreads page and found the #1 complaint to be the “Baroque” language, the intricately embroidered shades and nuances which some people said didn’t leave enough “white space.” How poorer would we be if everyone wrote like Hemingway?

Lucky for us, Elspeth Barker wrote The Book on dense prose crackling with specificity, a modern classic rich with the indignities of childhood.

But I’ve given away too much already. Read this book.

“A poetic and passionate description of adolescence. The words sing in their sentences. A world is evoked that has shades of the Brontë sisters and of Poe. . . . O Caledonia sets dreams and longing against Scottish righteousness and judgement, and the resolution is the blade of a skinning knife.” —The Times (London)

“A wonderful oddity—brief, vivid, eccentric, written with ferocious zest and black humour.” —Penelope Lively

“O Caledonia is like a bunch of flowers. Vivid images are handed to the reader one after the other and the colours are often freakish.” —The Guardian

Can't tell you how happy this makes me, to know that O Caledonia's magic is felt beyond the British Isles. I won't bore you with any 'pithy, ridiculous or obscure association I have to the book in question', although there are plenty, but my dear dead friend gave it to me shortly before her abrupt departure. I never had the chance to share with her all my pithy etc associations (which she hadn't known), nor to answer the Post-It note she stuck to its cover: 'Tell me what you think of it'. But the most ridiculous of associations may now be this, that her death in some ways brought me to Substack in the first place. Thank you for loving this book too.

Well, you certainly sold me on Barker with this wonderful piece, Troy. I’m gonna have to suss out her book. :)