Just back from 8 days in Dublin, which originally was supposed to be just three, with additional days in perhaps Galway and Cork, but as we started to examine Things To Do in those second cities we realized that they were not perhaps as attractive to us as we’d initially thought—not that The Butter Museum doesn’t have a special allure, but to actually pick up, repack, check out, train down, check in, and re-unpack just to look at churns and the history of butter wrappers? Maybe not.

We had been told that Ireland was best by car, but since my driver’s license expired and my husband was leery of driving on the left, we were certain that trains would be no problem. Wrong. Turns out even to nearby Kilkenny, the trains are sporadic; and day trips by motor coach all range from 12 to 13 hours with one exception which we will get to shortly.

Hell is trapped on a bus with strangers, so in the end we took a couple of field trips on the local train, one to the cliff walk of Howth Head, which brings us to the real ghost who haunts Dublin: James Joyce.

(The other ghost being, of course, Molly Malone. I learned her song in third grade, but confess myself disappointed by her statue in Dublin “where girls are so pretty,” her prominent bosom polished by decades of hands. This is a problematic tradition, when you think about it. There’s a mermaid here in Sitges similarly burnished, and I’ve read the statue of Juliet in Verona has been so overhandled she’s developed a hole in her right breast.)

By the way, Dublin’s “fair city”— while having a number of lovely buildings and parks—is also somewhat mannish in its charms.

Temple Bar is the district where most tourists hang out, and that’s certainly played up with pretty neogothic follies and gorgeous pots of petunias and geraniums hanging off every lamppost and windowsill—a feature you’ll see in almost every northern gray city—but on the whole, step away from the raucous live-music pubs (the screeching strains of a version of “Zombie” sent us fleeing) and you’ll find Dublin very much a working city with lots of plain brick houses and a fair amount of car traffic.

But back to Joyce: he’s everywhere, except in the cemetery, which brings me to an uncharacteristic defense of this undeniable literary icon.

Bearing in mind that he couldn’t find a publisher in Ireland; that when he did get published elsewhere, his books were banned in his native country; and that when he died in Switzerland, the government of Ireland refused his widow’s petition to repatriate his remains, it seems a little rich that now he haunts Dublin as a cornerstone of their culture. I mean, yes, his books all take place there, but it does feel a little bit like distant relations knocking on your door after you win the lottery.

(I’m reminded of Barcelona’s Gaudí, struck by a tram and left lying in the street for a beggar until it was too late, but now almost singlehandedly responsible for our local overtourism.)

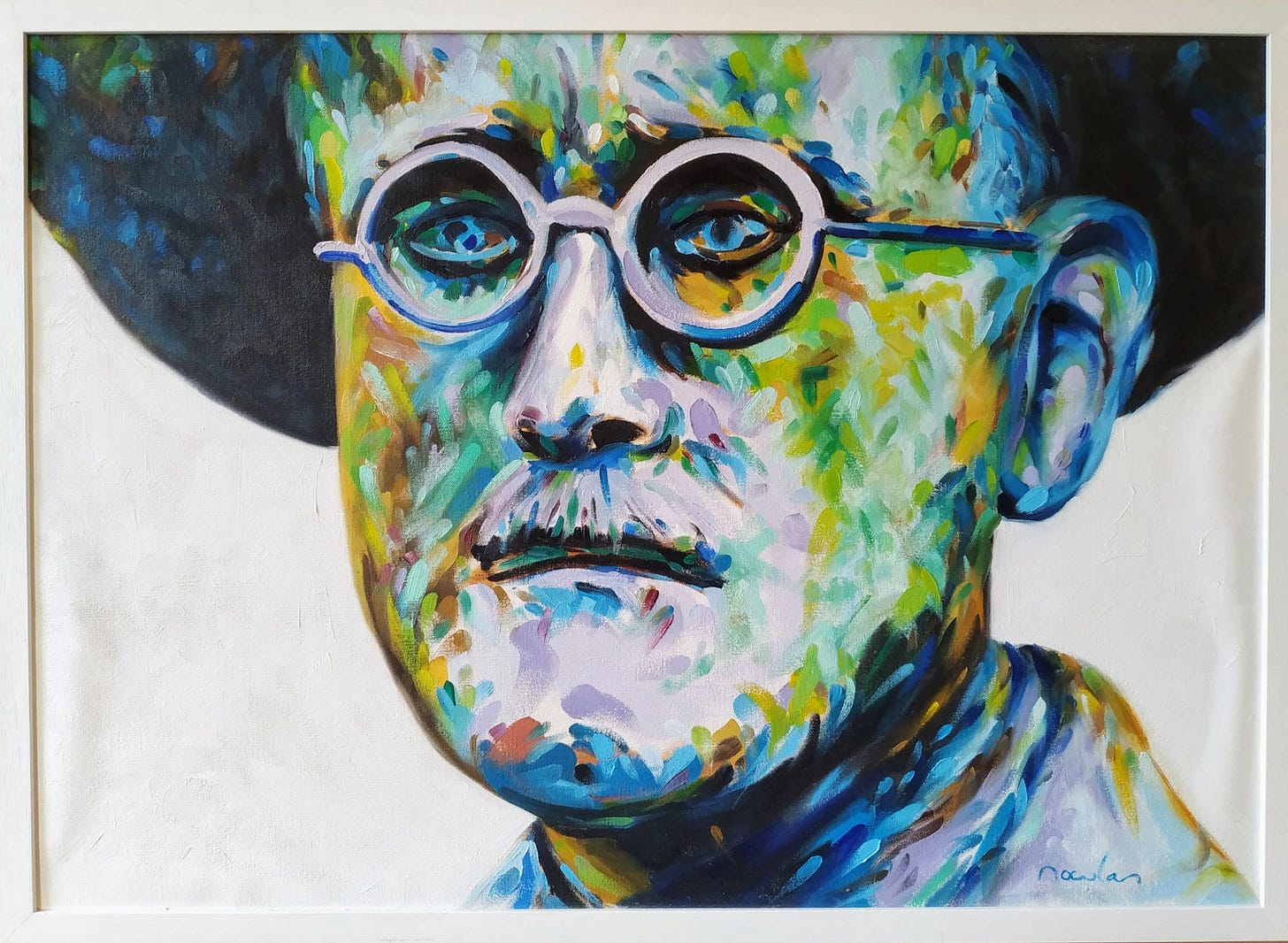

Of course our own hotel might have skewed my picture somewhat—if you want a James Joyce-themed hotel in Dublin, stay at the Motel One at the top of Lower Liffey Street, just up from Ha’penny Bridge.

Compliments to the interior design team: the graphics and decor are pretty nice; and as you can see in the pic, Joyce features prominently in the lobby, and the rooms—he’s really become a commodity of Ireland’s capital city in a way he most certainly was not in his lifetime.

But that’s Dublin in a nutshell, really—don’t judge a book by its cover and all that—they have a rich literary history, and they know how to use it in these latter days.

Besides Joyce, you’ll see mugs, keychains, and refrigerator magnets of Jonathan Swift (Gulliver’s Travels), Oscar Wilde (The Picture of Dorian Gray), Bram Stoker (Dracula), Samuel Beckett (Waiting for Godot) and others.

Ireland in general seems to have made quite the cottage industry out of its literary chops—there’s a mural on Moore Street which perhaps gives some slight clue as to its legacy of belle-lettres.

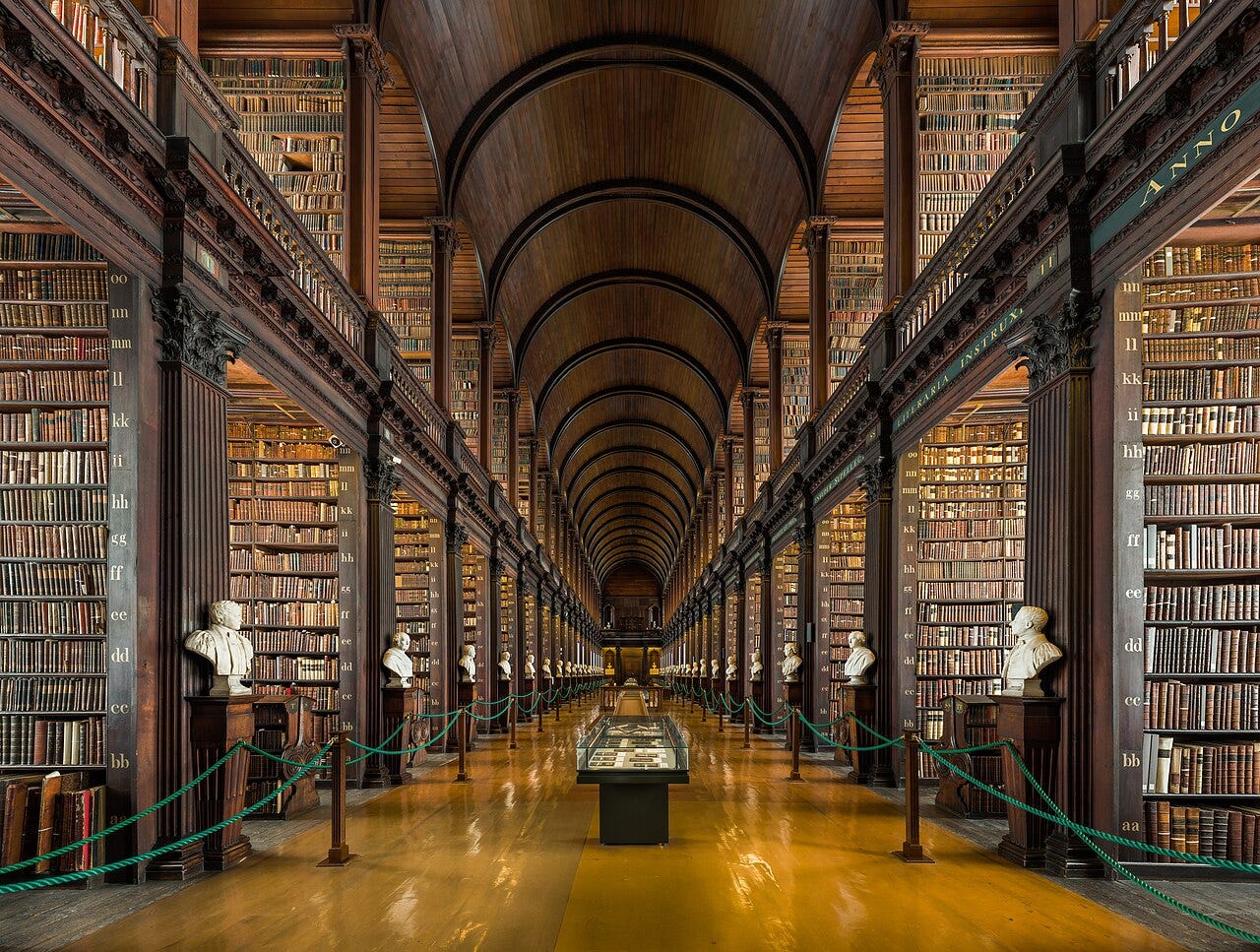

There’s the names, and then there’s the libraries.

The Long Room of Trinity College Dublin’s Old Library is in a period of transition: removing, digitizing, and restoring 350,000 books; in the meantime, the shelves are empty, and the gigantic artwork Gaia, while spectacular, isn’t quite the flavor one wanted.

(The ancient deer skeleton in Trinity’s Geology Building, on the other hand…)

The other highlight just downstairs, The Book of Kells, was recently turned to display a text-heavy page without illumination unfortunately, so it was a bit of a letdown, though after all it is just a Bible.

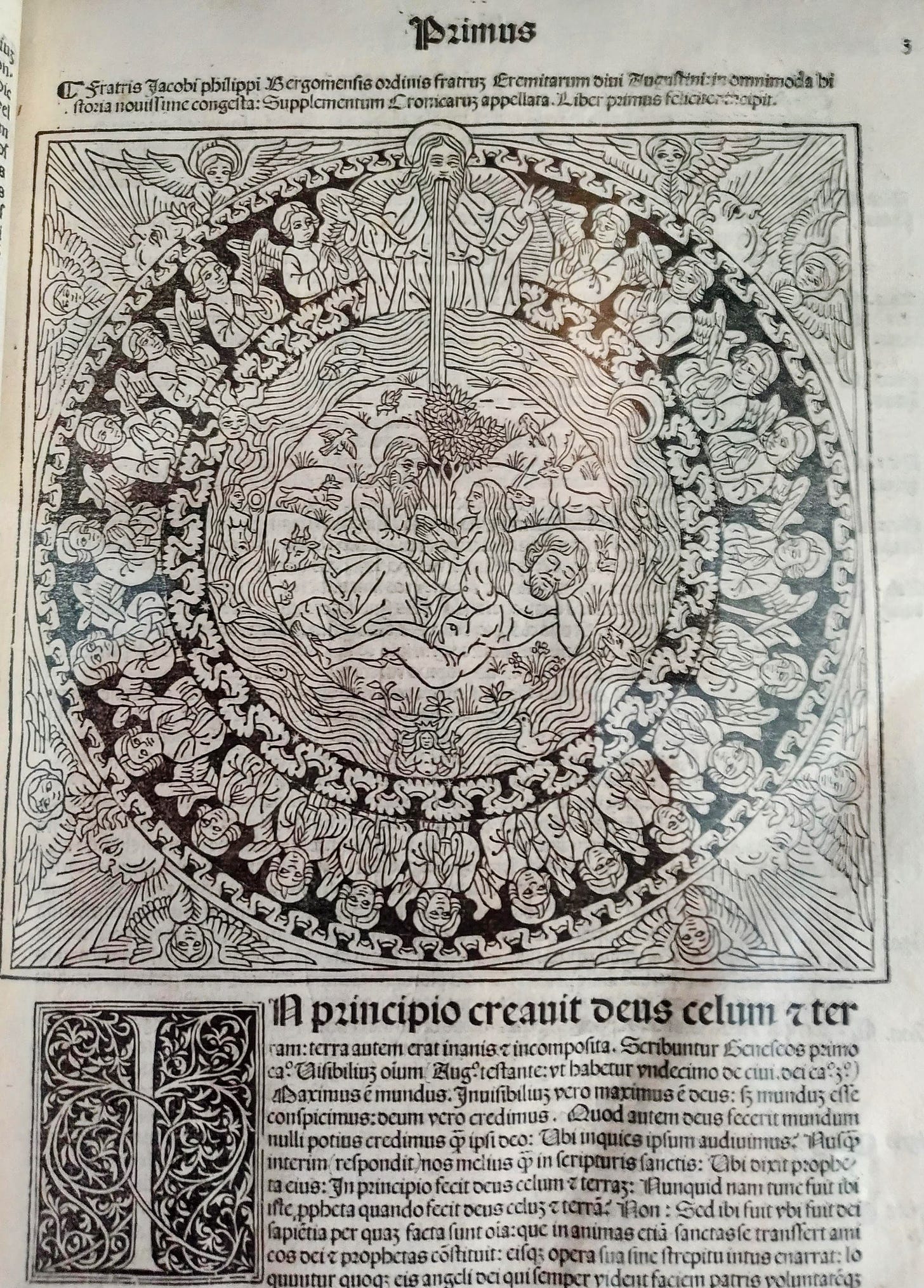

Meanwhile, the diminutive Marsh’s Library, tucked behind St. Patrick’s Cathedral, is a rainy-day bonbon with a fine collection of some of the earliest printed books (Gutenberg-era, Cicero’s Letters to Friends (1472) is their oldest) and some intact bullet holes from the Irish Civil War which the attendant will warn you not to stick your fingers into, though you may be tempted.

Of course, the Real Ireland I was searching for was the Ireland of Darby O’Gill and the Little People (1959), an iconic film of my childhood and the obvious confirmation to my young imagination that Brian Connors, King of the Leprechauns, was the inspiration for the King Under the Mountain of The Hobbit. The National Leprechaun Museum was just down the street from our ho/motel, but I was afraid it might be a Disneyfied version and not quite authentic so we didn’t go. (Regretting it now.)

However, since we definitely wanted to get out to the ruins and hills of the Emerald Isle in hopes of catching a glimpse or pot of gold, this was accomplished on a short motorcoach day trip to Glendalough (GLEN-duh-LOCKH), the remnants of an early medieval monastic city in a lovely valley with plenty of emerald, but no gold or hobbits I’m sorry to report.

Supplementary Notes:

Although we often skip guided tours, there’s always some interesting tidbit or other that the guides have picked up along the way, to wit:

Rented pineapples - Back in the day, even the wealthy couldn’t afford to actually eat pineapples so they just rented them for the centerpieces of their fancy dinner parties (thanks to our guide at Dublin Castle.)

The tenements of Dublin - Our guide on the James Joyce’s Dublin walking tour mentioned that while the Georgian townhouse in which the James Joyce Centre resides was at one time occupied by a single wealthy family, after the Great Famine, homes like this were often split up into tenements with as many as 10 families in a single room. The museum at 14 Henrietta Street is dedicated to this difficult time in Irish history.

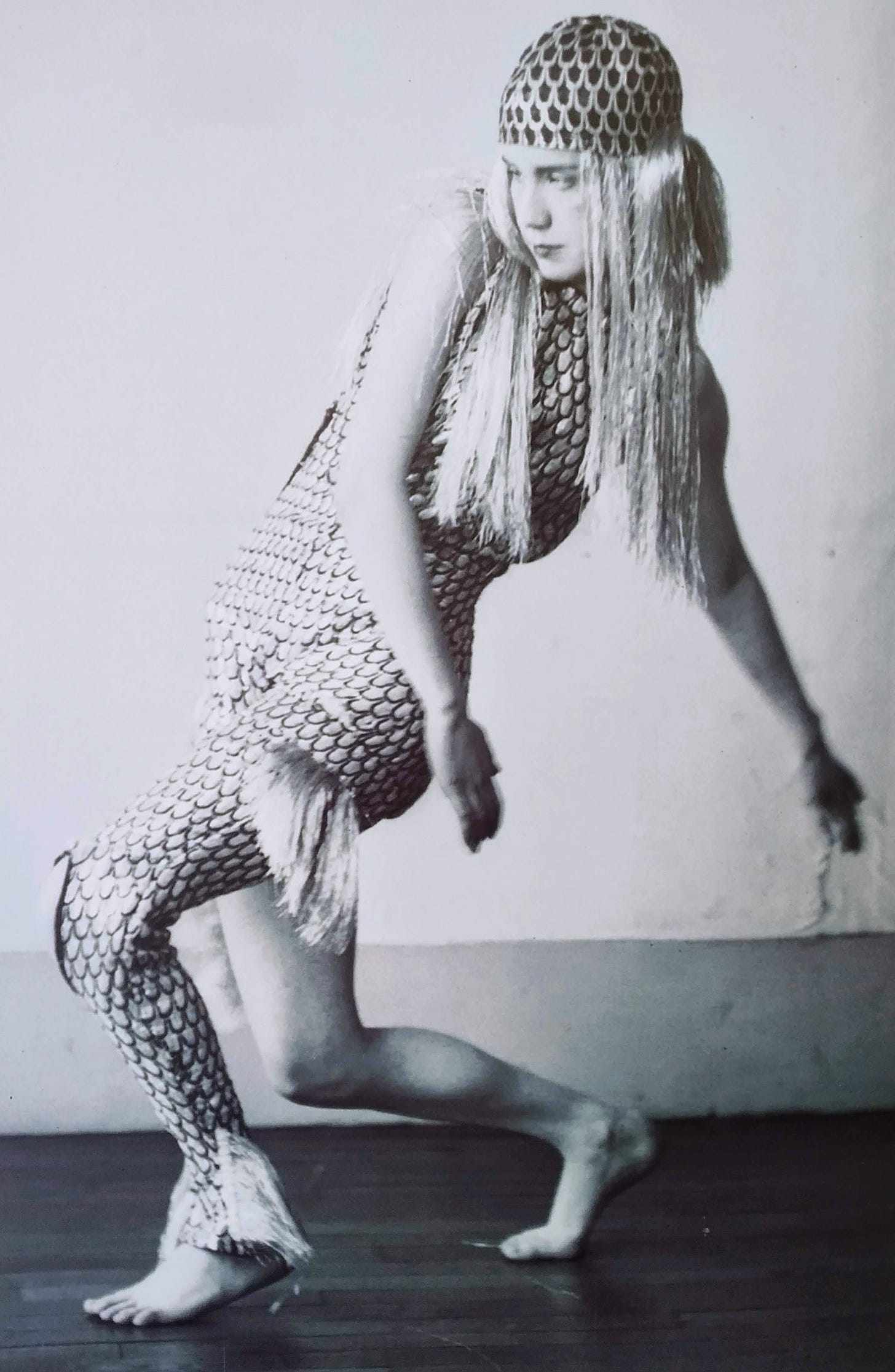

Lucia Joyce - James Joyce’s daughter was an accomplished modern dancer until her father pressured her to give it up, and she spent the last five decades of her life institutionalized.

Howth Head is the place in the last scene and last line of Ulysses where, to Leopold Bloom’s proposal of marriage, Molly recalls she said:

Loved reading this Troy, and all the photos! I want to know more about Joyce's daughter. She's beautiful.

I really enjoyed this, Troy. Your mention of trains in Ireland reminded me that trains had a special place in the work of another great Irish writer, Flann O'Brien: https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/going-loco-frank-mcnally-on-flann-o-brien-and-the-inchicore-railway-works-1.4875806. He's one of the funniest writers I've ever read.