I prefer not to remember my mother from the last time I saw her, after she fractured her hip tripping over a garden hose in the yard, because it’s not an especially happy memory of a not especially harmonious relationship.

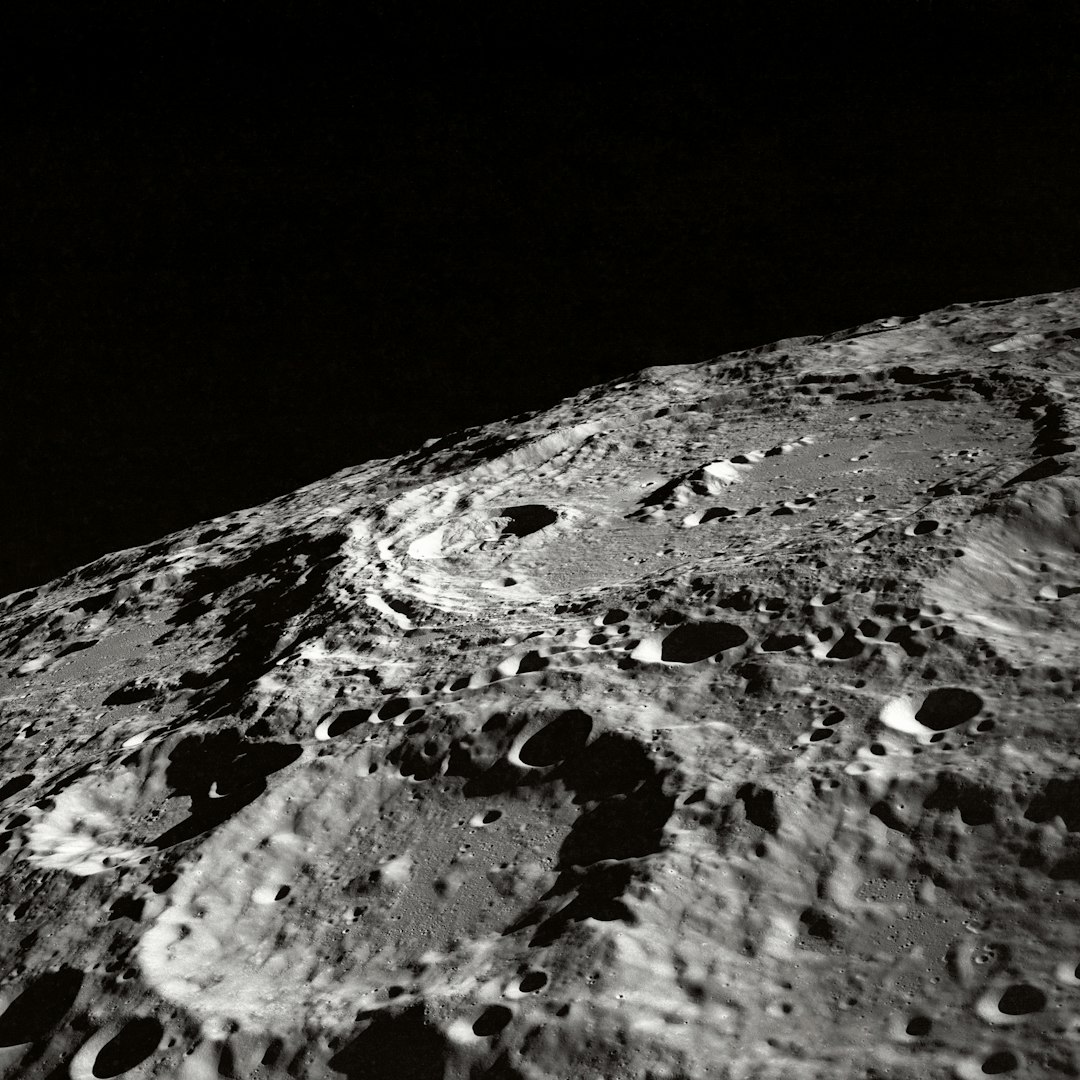

Just to be clear, it was a yard, never a garden—my mother did not “garden”—she worked in the yard, an enterprise which mainly consisted of weeding and complaining. The fewer plants the better, in my mother’s yard: flowers died, but weeds were forever, which suited her just fine. And so the expanse of lawn, and the riot of geraniums, gladiolas and sedum my grandmother had kept was slowly ripped out, block by methodical block once my parents moved in to Gramma’s after she died, until all that was left was a moonscape of gravel over a layer of black plastic to choke out the weeds, which found their way through anyway.

What she could have been watering out in that wasteland with the hose she ultimately tripped over is anyone’s guess. I wouldn’t be surprised if she was squirting one of the cats she constantly lamented were using her gravel as a litter box. Probably the cats’ scratching tore the plastic which allowed the weeds to grow and gave my mother something to do with her days.

In any event, the last time I saw or spoke to her, she was in a physical rehab center post-surgery to install a metal pin to stabilize her fractured hip. She was miserable, and as angry at the world as ever, and probably me too. I had hung up on her the last time we spoke when she started in with her usual harangue because I’d said it was a terrible idea for her to have bought my niece, her granddaughter, a car on her credit card after we had just gone through the whole rigamarole to refinance her house in order to pay off the $50K in credit card debt my dad had left her when he died.

“You just think you are so smart—” she started, and well, I’d heard that one just one too many times before.

I immediately dashed off a note of apology after the hang up, which produced an immediate written reply, and I admit I didn’t have the stomach to open it for months and months, and in the end shredded it unread, which I regret now but there were really only two probable replies, another “you just think you are so smart” or polite forgiveness, and honestly, “polite” had fallen by the wayside after my father left her less than penniless, so I thought it far safer to maybe miss a faint forgiveness in order to avoid all but certain vitriole.

Anyway, it was tough seeing her at the rehab center where she was confined to her bed or a wheelchair for the duration because it was not like a retirement home with a common area and activities, it was just a hospital ward. I flew down on a Saturday morning, and ran into my sister coming out as I was heading in.

“She seems OK,” she said, “but you should ask her about her jewelry. I tried to find it but I couldn’t be too obvious with them all there watching me.”

Despite my grave warnings, my sister’s daughter was back living at grandma’s with her second baby (the first one had kinda sorta been abducted by the other father and folded into a network of relations running from San Juan Capistrano down to Mexico,) and had moved not just her current baby daddy but also his mother into our mother’s house while she was in the hospital. OK. See you later, my sister had to get home to her two new kids, the ones she intended as redemption for her magnificent failure to raise her first one—“The Cause” as she liked to call her familial enterprise, which financed itself through child support payments and donations for an impromptu animal rescue.

I rolled my deflated mother out to the dusty picnic table wedged graciously into the parking lot at the end of the facility. All was (mostly) forgiven.

I still smoked, then. “I suppose you aren’t gonna let me smoke, either,” she said, her eyes guarded. I don’t remember what we talked about, but I do remember the silent gratitude when I shared my cigarettes. We smoked two or three together, and before I left, I gave her the rest of my pack and lighter; she was visibly relieved.

“What do you want me to do with your jewelry?” She had put it in the big spaghetti pot in the kitchen, knowing my niece would never find it, but now that mama baby daddy was on the scene she just might dig it out to make a big pot of beans and find the cache of good 22K gold still left from our Saudi Arabia days. I asked if she wanted me to retrieve it and bring it to her there at the hospital. No, no—go get it and take it home with me, back to the Bay Area, and I could give it back later.

When I popped round the house and let myself in with her key, there was indeed a strange woman sitting on the sofa watching TV with a baby I could only assume was my great-nephew, though we had never met. “Hello,” I said, to a blank if unsurprised stare. The jewelry was just where she said, in a white case in the big pot, back of the bottom cabinet next to the stove. I wasn’t there more than thirty seconds, didn’t bother to say goodbye, but just in that short moment, my niece arrived home with her baby daddy, and they were in the street admiring the rental Mercedes I had got with a free upgrade; literally, they were walking around the car as though looking for anything loose.

Her eyes lit on the white jewelry case in my hand and widened in surprise; I assumed she had been searching for it. I barely broke my stride. Nice to see ya, kiddo, stay out of trouble.

So like I said, it was the last time I saw or spoke to my mother (or my niece or sister for that matter.) By the time Mom got home, my niece had had time to fester about the jewelry she could have pawned and was screening all my calls. Maybe six months later, my sister called the cops and had her daughter arrested for elder abuse (financial exploitation) and when she phoned to say she was moving Mom up to an elder care home she’d wrangled for free through the state, she asked me about the gold.

“Did you jack Mom’s jewelry?” I beg your pardon? Apparently, her daughter had sold everything out from under our mother except the chair she was sitting on, “but she said she saw you leaving the house with mom’s jewelry case.”

“You mean the jewelry you mentioned you were afraid she was going to steal and which mom sent me to her house with her key to retrieve and keep safe with me up here, that jewelry?” There was a long pause as my sister searched her fried egg of a memory. “So yes, I have it, and when mom wants it, she just needs to let me know and I’ll bring it down—to her—next time I visit.”

There never was a next time. While my sister also festered about the missed opportunity of the Saudi gold, I never did get the name or phone number of the facility where my mother had been installed. She died of a stroke another six months after that. There was no memorial service, as far as I know.

The way I choose to remember my mother is from a family Christmas at my aunt’s some years before. I think it is impossible she ever saw the Polaroid because it was incredibly unflattering and if she had seen it, she would have slipped it into her purse and cut it into fifty million little pieces quietly at home.

It is the most charmingly, amusingly, candid photo of her doing what can only be described as her impression of a chicken: her wrists hitched up to her side, elbows bent, wings flapping; her mouth puckered into a laugh of a beak of a cockadoodledoo; her head thrust up in what can only be described as a moment of pure silliness. So very, very unlike her, so utterly out of character, and yet, there she is, my mother the chicken.

I am unaccountably glad because I only vaguely remember the moment. She was capable of real fits of genuine laughter at times. It is pure magic the picture was captured in the first place, and even more that it survived. How it came into my possession I have no idea, but it stands in my memory as the antidote to the bitter puzzle of all those final missed, unread, unanswered messages to each other.

Very touching. I understand well the complexities of difficult family dynamics but could never desccribe it so well in words. This story spoke to me on a profound level. Love and light to you!

What a story. Could be a short film. My relationship with my mother was much more conventional. There was jewelry too. But, in my case, no one wanted it! So, of course, the inevitable question is: whatever happened to the Saudi gold?